On October 14th all Australians have an important decision to make.

There has been a lot of divisive and harmful talk in recent weeks as we’ve headed to the referendum on the voice.

I’d like to put that aside and talk about some of the basic psychology and why I’ll be voting Yes. I also really want to encourage other Yes voters to understand that voting Yes is not enough. The odds are stacked significantly against us, and we have to be out there, talking to the 30% of people who’ve not made up their minds. If we all change one person’s mind to a Yes vote, we will win.

The game is rigged

Peter Dutton (leader of the opposition, and declared No supporter) has made some comments that the vote is ‘rigged in favour of yes’. I agree it is rigged, but not the way Mr Dutton claims.

The referendum is asking for change, it is asking for a voice to be granted to people who do not have one today. I agree the game is rigged, but it is rigged against the Yes campaign because of the high bar we need to get over and some deeply ingrained psychological biases that all humans have.

Winning is hard

To win a referendum in Australia, you need what’s called a ‘Double Majority’, this means getting a national majority of eligible voters as well as a majority of voters in at least 4 of the 6 states.

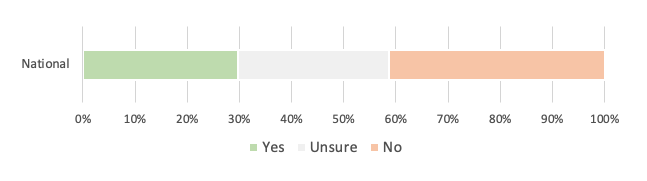

The chart below shows the magnitude of what stands in front of the Yes campaign, nationally roughly 30% of people are on the Yes side, about 30% of people are unsure and the remaining 40% are on the No side.

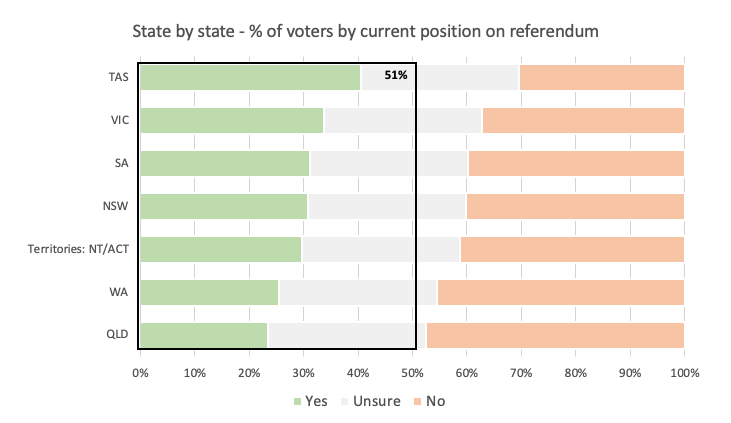

If we assume Yes and No aligned voters have already made up their minds, it leaves the unsure/on the fence people who will make the difference between Yes winning and losing. Because of the high bar of the double majority, it will take 75% of unsure voters in the closer states (those with the smallest gaps between Yes and 51%, being: NSW, VIC, SA and TAS) and 60% of those voters in the other two states (QLD and WA). Even this would only land at a national vote of 50.1%, which is just ‘squeaking’ over the finish line.

The picture below shows how hard this is, if Yes had to win a consistent 51% across all the states and territories it means capturing more than have of the unsure voters in most states and in WA and QLD this means getting more than 90% of unsure voters to vote Yes.

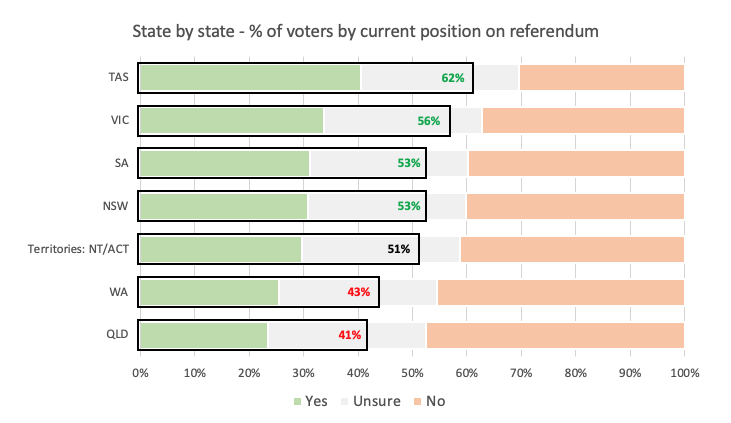

Because this is a very unlikely scenario, it means significant over-performance in the stronger states for Yes and still greater than 50% of unsure voters voting Yes in the weaker states.

Notes:

- This chart is based on state by state data available here and is an average of the last 4 polls

- There are no ‘unsure’ numbers in the state by state data and so I combined it with data from here to get this view

- Enrolled voter numbers came from here

My scenario explained in the narrative above is visualised on the same chart below, it meets the double majority criteria, and is still a big mountain to climb.

My case is that this is an especially hard scenario when you take into consideration how the campaigns are running, and the general tendencies of humans to make choices which favour inertia.

Let's have a look at some of the most relevant tendencies.

Preference for the Status Quo

The status quo bias is a finding from behavioural economics and was written about in Nudge and Misbehaving by Richard Thaler. It is evident when people prefer to see things remain the same through inaction or by sticking with a previously made decision - even when the transition costs are low or there are significant implications to the decision.

This bias can come about when people stick with the ‘safe decision’ made in the past when they are faced with information overload, when people hit their cognitive limits they are more likely to ‘stick with what they know’ rather than explore the details of the choice.

I see that many of the current arguments that are being made, especially by the No campaign, involve complex counterfactuals which talk about what might happen in the future as a result of a Yes decision. These take considerable effort to understand and I expect that more than a few people may just decide it is all too hard and say No.

Endowment Effect

The endowment effect says we will value an object (or state) we currently have at a higher level than we would pay to acquire that same object (or state) if we did not already have it. This same effect has been extended by Prospect Theory to show that generally speaking, people are risk seeking for potential gains, but risk averse for potential losses.

This is relevant here because the more the implications of a Yes vote are framed as potential losses for unsure voters, the more likely they are to be ‘risk averse’ and again ‘stick with what they know’ and vote No.

Reading the 10 points the ‘No’ campaign have put in their pamphlet, at least 6 are raising potential losses and/or ambiguity which can be framed as losing something people perceive they have certainty of today. This is active exploitation of this way that humans think.

Framing

Will you buy a cleaning product which has a 20% chance of harming you? Or an 80% chance of not harming you? In both cases the expected outcome is the same, as the probability of harm is the same, but the framing is different and you are more likely to say yes to the second framing than the first.

Framing effects can be found in lots of places, especially on food packaging (think 80% lean vs 20% fat - which sounds better?)

Again, much of what is presented in the No case is framed negatively and as losses, which will evoke powerful responses from readers who will seek to be risk averse in the decisions they make in those negative frames.

Coherence

When we are asked to make decisions about abstract concepts, our brains translate those questions into simpler ones. This can serve us very well, and most of the time it does, however the kicker is that most of us are unaware that we are not really answering the question we were asked.

There are several biases that come into play in this process, however one very relevant one is that coherent stories (and options) tend to come across as more plausible, and when we are being to vote Yes or No, we might actually be evaluating internally which side’s argument we find to be more coherent - and things that are simple to understand are generally considered more coherent.

As I’ve mentioned earlier, much of what has been written about the Voice is complex, although the No side have landed on a very simple message of saying: “if you are not sure, you should vote against it”. I think this gives No an advantage, it is simple, and simple fits well with coherence.

So What...

I wrote this to try and bring to people’s attention that Yes is far from in the bag, and that it has to pass a pretty high bar. When you consider the weight of human behaviour (and to some extent apathy), that bar just gets higher.

Ultimately, I’m voting Yes because I am not aware of a single time in human history where accepting a broader range of inputs and opinions in any decision making process has led to a materially worse outcome for society in the long term. We are a pluralistic society, that means we accept more than one viewpoint, and we should have more of those, not less.

If you are also a Yes voter, then look at the numbers and realise that just voting Yes is not enough, you need to be talking about why, and trying to change minds where you can.

If you are unsure, then think about why you’d vote No, and if it is related to some of the things I’ve raised then ask yourself, have you really engaged with the facts?

Consider the very difficult task in front of the Yes campaign, consider if you are really giving anything up by voting Yes - I'd posit you are not giving anything up, that the 'transition costs' are low - but that the opportunity cost of inertia is very, very high.

-- Richard, Sep 2023